Guardrails that prevent DAG chaos (and stop “Gold consuming Bronze” by accident)

In Story 1, I shared the painful lesson we learned in production: topic-slicing alone isn’t enough. If you don’t separate a data product by Topic × Medallion, your orchestration graph becomes fragile and your blast radius gets out of control.

Now comes the platform engineer’s version of the same lesson:

A model that isn’t enforceable becomes optional.

Optional rules become “best effort.”

Best effort becomes chaos the moment you scale.

So Story 2 is about the practical question I got immediately after sharing Story 1 internally:

“Cool. But how do we prevent teams from wiring Gold to Bronze at 2 a.m.?”

Here’s the answer: you turn Topic × Medallion into guardrails.

Not documentation. Not tribal knowledge. Guardrails.

This post breaks down the minimal set that actually works.

The core idea: constrain the graph before it becomes a spaghetti bowl

When DAGs go bad, it’s rarely because your orchestrator is weak.

It’s usually because your platform silently allows:

- the wrong dependencies,

- the wrong exposure patterns,

- and uncontrolled drift.

So the goal isn’t to “build a better DAG UI.”

The goal is to make bad graphs unrepresentable.

A good platform enforces three things:

- What a product is allowed to expose (output ports by maturity)

- What a product is allowed to consume (subscription/dependency matrix)

- Where enforcement happens (CI gates + runtime checks)

Let’s unpack those.

Guardrail #1: Output ports are policy boundaries (not “just outputs”)

Once you adopt Topic × Medallion, you’ll naturally end up with product slices like:

- Topic A – Bronze

- Topic A – Silver

- Topic A – Gold

From a platform perspective, each slice needs a clear rule:

Which output ports are allowed for which product type / medallion slice?

Because if you allow “anything exposes anything,” you’re back to mixed promises.

A practical pattern: product types + allowed ports

Define a small set of product types (don’t overdesign this):

- Source-aligned / Ingestion (raw, traceable)

- Core / Standardized (clean, consistent keys, deduped)

- Consumer / Serving (semantic stability, KPIs)

Then define allowed ports per type. Example:

- Ingestion type → can expose Bronze

- Standardized type → can expose Silver

- Serving type → can expose Gold

This does two things immediately:

- It prevents “serving products” from leaking raw outputs.

- It forces teams to be honest about maturity promises.

Important: This is not governance theater.

This is how you keep the graph readable and the blast radius controlled.

Guardrail #2: Allowed upstream subscriptions (the dependency matrix)

This is the one that saves you from the nastiest failure mode:

A downstream “Gold” product consumes an upstream “Bronze” port because it was “quick.”

That “quick fix” becomes permanent, and months later nobody remembers why a KPI depends on raw ingestion behavior.

The subscription matrix

You implement a simple matrix:

Downstream type/medallion → allowed upstream type/medallion

Example (simplified):

- Silver may consume Bronze (same topic family, controlled)

- Gold may consume Silver only

- Gold consuming Bronze is blocked

This is the single highest-leverage enforcement you can add.

Because most DAG chaos comes from shortcut dependencies that bypass maturity.

If you only implement one guardrail, implement this one.

Guardrail #3: DAG hygiene rules (keep it operable, not just valid)

Even with port and subscription constraints, graphs can grow in unhealthy ways.

So you add “hygiene” constraints that don’t dictate architecture, but prevent pathological cases:

Good “platform hygiene” rules

- No cycles (obvious, but enforce it mechanically)

- Max dependency depth per product slice (prevents “everything depends on everything”)

- Explicit backfill boundaries (reprocessing must not cascade uncontrolled into serving layers)

- No fan-out storms without explicit approval (one upstream change triggering 50 downstream refreshes)

These rules exist to protect the platform from accidental complexity.

They keep on-call life sane.

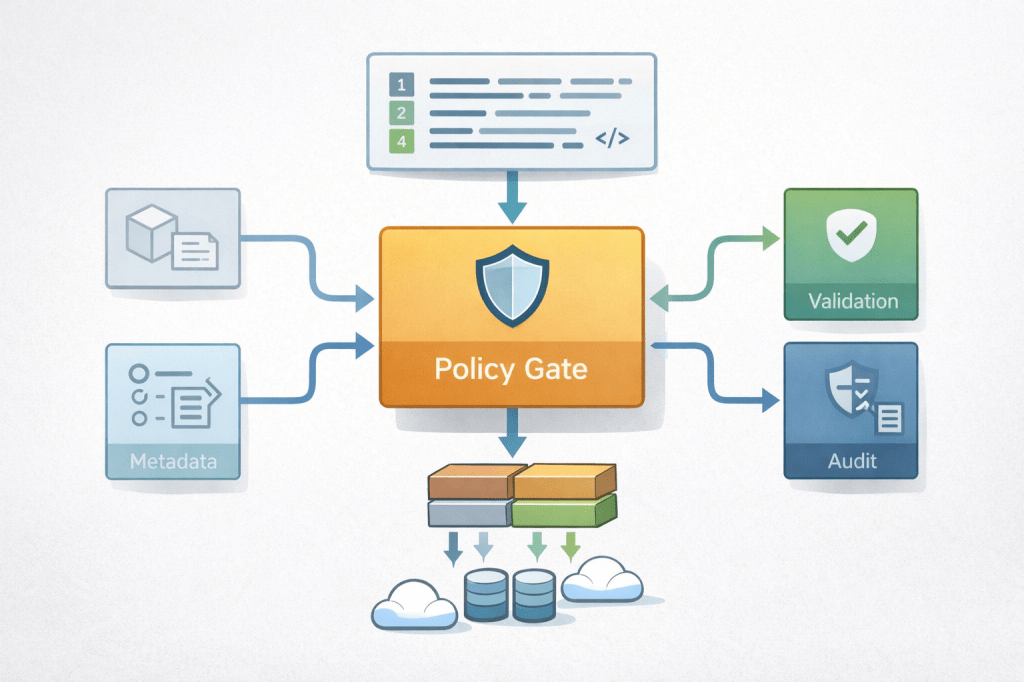

Where enforcement lives: the 3-layer model

Guardrails fail when they only exist in a wiki.

They work when enforcement is layered:

1) “Design-time” checks (PR / registration)

When someone defines or changes a product, you validate:

- product type

- medallion slice

- output ports

- declared upstream subscriptions

Outcome: bad designs never get registered.

2) “Publish-time” checks (deployment gate)

Before anything becomes active in “live”:

- validate the dependency graph

- validate compatibility and contract status

- validate policies (ports, subscriptions, lineage completeness)

Outcome: no “oops, it’s live now.”

3) “Run-time” checks (protect production behavior)

Even with CI gates, runtime drift happens:

- someone changes a schema out-of-band

- an upstream starts producing late events

- a backfill triggers a refresh storm

So you add runtime enforcement:

- detect drift

- block dangerous triggers

- quarantine questionable outputs

- notify owners with actionable context (impact radius)

Outcome: production is resilient to reality, not just to best intentions.

The minimal implementation blueprint (that doesn’t take a year)

If you want to get real value quickly, this is the “minimum viable guardrails” order I recommend:

Phase 1: Subscription matrix + graph validation gate

- Store allowed upstream rules centrally

- Block Gold → Bronze dependencies

- Validate DAG: no cycles, dependency depth limit

This alone reduces chaos dramatically.

Phase 2: Allowed output ports per product type

- Standardize product types

- Enforce port exposure rules

This reduces maturity mixing and contract ambiguity.

Phase 3: Runtime drift + blast radius reporting

- Detect contract/schema drift

- Show “who is impacted” when something changes

- Add quarantine / safe-mode options for serving layers

This reduces incident duration and restores trust faster.

Handling exceptions (without destroying your own rules)

Every platform has exceptions.

The trick is: exceptions must be explicit, time-boxed, and auditable.

A simple approach:

- Allow an override flag for a blocked dependency

- Require an owner + rationale + expiry date

- Emit an audit record

- Make the platform remind you before expiry (and block after)

This keeps rules strong without blocking delivery.

What changes culturally when guardrails exist

This is the unexpected benefit:

Once guardrails exist, conversations become sharper and less emotional.

Instead of:

- “Why are you blocking me?”

- “We need it urgently!”

You get:

- “We want Gold to consume Bronze — which rule would that violate?”

- “Do we actually need Gold, or should this be a Silver consumer?”

- “Is this a temporary exception or a missing product slice?”

Guardrails turn architecture debates into product decisions.

That’s exactly what you want.

A simple “definition of done” for Topic × Medallion enforcement

If you want a crisp internal checklist, here’s one:

You’ve “made it enforceable” when:

- Gold → Bronze dependencies are mechanically impossible (without time-boxed override)

- Every product slice declares its upstream subscriptions explicitly

- Output ports are validated against product type

- DAG health checks run automatically on publish

- Runtime drift triggers show blast radius + owner routing

If you have those, you’re no longer hoping teams behave.

You’re engineering the platform so they can’t accidentally do the wrong thing.

Next episode: contracts that consumers actually trust

Once Topic × Medallion is enforceable, the next question becomes:

What do we actually promise consumers per layer—and how do we version that promise?

That’s Story 3:

- Bronze vs Silver vs Gold contract promises

- breaking vs non-breaking changes

- a simple contract template people will actually use

Leave a comment